The H5N1 vaccine had already been manufactured at the Seqirus facility and stored in precise conditions, with temperatures maintained between 35.6 and 46.4 degrees Fahrenheit. These concentrated doses are produced in advance and held as part of the national stockpile, ensuring preparedness for potential public health emergencies.

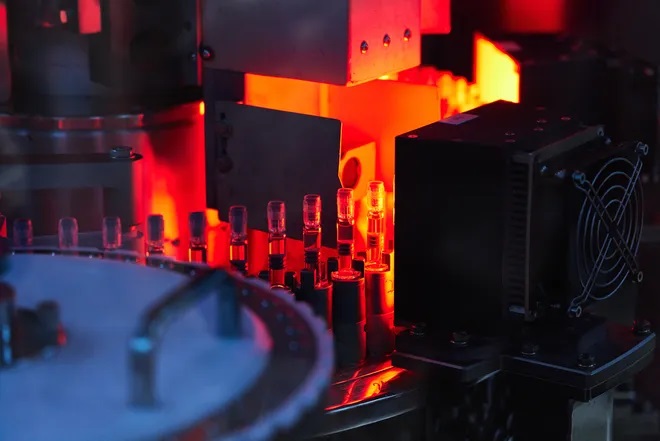

Now, the vaccine has been poured into vials, making it easier for public health officials to swiftly distribute doses if the need arises. This proactive step enhances the ability to respond quickly and effectively should the H5N1 virus pose a significant threat to human health.

Producing the substance for the H5N1 vaccine doses is a meticulous process that takes about a month. Afterward, it takes an additional day to formulate each batch, another day to fill the vials, and a final day to inspect and package them. This entire process is part of Seqirus’ effort to produce all 4.8 million doses under a $22 million agreement with the federal government.

To defend against the H5N1 virus, two types of vaccines are being prepared. Alongside the traditional, cell-based vaccine being produced at Holly Springs, the government has also allocated $176 million to Moderna to develop mRNA influenza vaccines, including one for H5N1.

These two vaccines utilize different technologies. The mRNA vaccine, which can be produced more quickly, is ideal for situations where a pandemic is spreading rapidly. On the other hand, the more traditional cell-based vaccine, which is currently rolling off the assembly lines, takes longer to produce but has already been stockpiled as a preparedness measure.

Dr. Nahid Bhadelia, the founding director of Boston University’s Center on Emerging Infectious Diseases, noted that it makes sense to complete the cell-based vaccines that are already in the national stockpile. She explained to USA TODAY that an mRNA vaccine could be crucial if the virus mutates significantly, necessitating the development of a new vaccine.

Despite the ongoing efforts, Dr. Nahid Bhadelia, who previously served in the Biden administration during the COVID-19 pandemic, expresses concern that Congress has not allocated sufficient funding to stay ahead of the bird flu virus.

“Nothing can happen without money,” she emphasized, highlighting the critical need for adequate resources to ensure preparedness and response capabilities in the face of a potential pandemic.

The Vaccine We Have Now

Scientists are hopeful that the vaccine currently being poured into vials will protect against severe H5N1 infections, but they can’t be entirely certain just yet. So far, this new vaccine has only been tested in ferrets, the standard animal model used by labs to evaluate flu vaccines. While Seqirus already manufactures an H5N1 vaccine deemed safe and effective by the FDA, this new version replaces the previous H5N1 strain with the currently circulating virus.

Human trials for this updated vaccine have recently begun, starting with healthy individuals to determine whether the vaccine effectively triggers the desired immune response. Results from these trials are anticipated later this year.

Although researchers believe the vaccine being produced will be effective against the current strain of H5N1, it’s not a guaranteed outcome, as Dr. Nahid Bhadelia cautioned. The ongoing trials will be crucial in confirming the vaccine’s efficacy.

It’s also possible, according to Dr. Paul Offit, an infectious disease and vaccine expert who directs the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, that by the time the H5N1 virus mutates enough to pose a significant threat to large populations, it may have changed so much that the current vaccine being prepared will no longer be effective.

Even if the vaccine does prove effective, there remains the challenge of scaling up production and distributing it to a large number of people quickly. The vaccine requires two doses, administered at least three weeks apart, for optimal effectiveness. However, it is still unclear how much protection a person receives after just the first dose. Seqirus, in emailed responses, declined to specify when the vaccine doses expire and when they would need to be replaced.

Delivering these vaccines to people presents its own set of challenges. The COVID-19 vaccine rollout highlighted unexpected difficulties in transporting doses from warehouses to clinics and getting them administered. Issues such as cold storage requirements, bottle sizes, and logistical hurdles had to be addressed in real-time, illustrating the complexities involved in vaccine distribution. These challenges are likely to arise again if the H5N1 vaccine needs to be rapidly deployed.

The National Biodefense Plan, launched in 2022 under the guidance of Dr. Raj Panjabi, was created with a clear goal: to ensure that enough vaccines are available for all at-risk populations within four months of a pandemic’s onset.

If the bird flu could be contained early—prevented from spreading beyond farmworkers, their families, and into the general public—it would significantly simplify the task of producing and distributing enough vaccine within that critical four-month window. Early containment would not only ease the manufacturing process but also ensure that vaccines reach the most vulnerable populations swiftly, potentially averting a wider health crisis.

This is why some public health experts advocate for offering vaccines to farmworkers before the virus has a chance to evolve into a more dangerous threat.

Dr. Nahid Bhadelia believes that vaccinating farmworkers may not necessarily reduce the overall number of severe bird flu infections. However, she argues that they should be offered the vaccine as part of a research trial. “It will just potentially help with severe disease and further our scientific understanding,” she explained.

Despite these concerns, Dr. Nirav Shah, principal deputy director for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, maintains that it’s not yet the right time to begin vaccinating anyone.

Dr. Nirav Shah emphasized that, at present, the H5N1 virus has not caused severe disease, is not spreading from person to person, and its genetics have remained largely unchanged since the vaccine was developed. During a press briefing in late July, Shah explained that a readily available antiviral treatment is currently a more effective tool for those infected or exposed to the virus than the vaccine.

“The H5 vaccine, at this moment in time, is not performing the job that we really need,” Shah stated, underscoring the current focus on antiviral measures over vaccination.

A Different Vaccination Approach

Finland took a different approach to addressing the threat of H5N1. In June, Finnish officials began distributing 20,000 doses of a different Seqirus vaccine to people aged 18 and older who were exposed to animals believed to be susceptible to bird flu, including workers in the country’s mink industry.

By late July, fewer than 200 people in Finland had received the vaccine, and there’s a looming deadline, as the vaccines must be administered by mid-September before they expire. Mia Kontio, chief specialist for the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare’s infectious disease control and vaccinations, noted that many Finns are on vacation during the summer, making August a “very hectic” period to ensure that people receive the full two-dose regimen in time.

The imminent return of wild migratory birds in the fall, which may carry the virus, adds to the urgency of the situation, according to Mia Kontio.

“We felt that it’s our responsibility to actually do something if we can,” Kontio told USA TODAY. “Because the situation might change very quickly.” This underscores the importance of acting swiftly to protect those at risk as circumstances could evolve rapidly with the changing seasons.

Where Are We Now?

In the United States, federal officials have taken several steps to mitigate the spread of the H5N1 virus. Recent months have seen expanded regulations on the interstate transportation of livestock, as well as increased alerts on products like unpasteurized milk, which could potentially carry the virus. Officials have also emphasized the risk of shared equipment spreading the virus among animals.

To further protect those in affected areas, the government has distributed personal protective equipment (PPE), including N95 respirators, goggles, and gloves, in states impacted by bird flu. These measures aim to reduce the risk of transmission and safeguard both workers and animals as the situation continues to develop.

Recent Efforts and Precautions

Recently, federal officials initiated a campaign to vaccinate livestock workers against the seasonal flu. Although this vaccine does not provide protection against H5N1, which is a different strain of influenza, it plays a crucial role in preventing other potential complications, according to Dr. Nirav Shah from the CDC.

Shah explained that receiving the seasonal flu vaccine could help prevent individuals from contracting both the highly contagious seasonal flu and the dangerous H5N1 simultaneously. The worst-case scenario, he warned, would be the emergence of a virus that combines the characteristics of both strains, posing a significant threat to public health. This precautionary measure aims to reduce the risk of such a development while ensuring that workers are protected against the seasonal flu.

Flu viruses have the ability to exchange genes with one another, making such a combination a real possibility.

“Viruses are sort of smart,” said May Chu, a clinical professor of epidemiology at the Colorado School of Public Health, in an interview with USA TODAY. “Our bodies provide the environment where they replicate. So, if you don’t let the virus into your body, you won’t contribute to the genetic evolution of the virus. This is crucial to stop, because the more people get infected, the more the virus multiplies, increasing the chances of a harmful genetic variant emerging.”

Chu emphasized that a combination of flu strains would be “bad for us,” highlighting the importance of preventing infections to reduce the risk of such dangerous mutations.

Don’t miss our comprehensive coverage of related topics, available on our Digital Platform.